A neighbor was sweeping his sidewalk, pushing tiny white rocks back into his rock garden. The sky was an uninterrupted blue. A mailman worked his way up the empty street. There were no signs of “Sharia Law.” The migrant caravan was still hundreds of miles away in Mexico. Antifa protesters had yet to descend on Pahrump. Chapian squinted against the sun, closed the shades and went back to her screen.

— Description of Shirley Chapian, consumer and believer of near-apocalyptic right-wing disinformation, from ‘Nothing on this page is real’: How lies become truth in online America (WaPo)

I have a few thoughts on the recent Washington Post piece on misinformation, which follows both a purveyor of it and a consumer of it. I’m breaking those thoughts into a few posts. This is number one.

It’s a doozy.

One note — I should be clear to people reading this who don’t know my deep hatred of conspiracy theory — 9/11 happened. Charlottesville happened. The Access Hollywood tape is real. If you think otherwise you’re a bit of a dope. That’s the whole point of using the examples I use below.

It’s amazing I have to say this stuff, but I choose these events as examples because they are real and yet our experience of them is surprisingly ungrounded, and that level of ungroundedness presents cultural vulnerabilities that are exploited by bad actors. Stick with me, folks. Read it to the end.

Facts and Downstream Beliefs

In misinformation, you’ll often hear it said that “facts” don’t really change downstream actions much.

This is true, in a very contained sort of way. If you believe nuclear power is safe, and I show you evidence it is not and then ask you what you think we should do about nuclear power, the chances are your answer will not change much. In fact, your knowledge may increase, but your larger beliefs about nuclear power will likely not move, at least in the short term. This is one of the more established facts of political science.

People are really resistant to changing their minds (unless, of course, you tell them a new idea is what they have always thought, but more on that in later posts). We have a status quo bias of sorts when it comes to our identity, and we’re not going to start ripping up the floorboards of our self-conception because someone forwarded us some new press clippings. Identity and experience is what really shifts our thinking, and as such people are (rightly) skeptical that headlines reading “California Wildfires due to Global Warming Say Experts” are going to turn us all into a cap-and-trade evangelists.

But reading the Washington Post story, I think it’s clear that this model of disinformation — as primarily changing beliefs — is wrong for much of what’s going on.

Experience Alters Identity, and Identity Action

Did 9/11 change you? It changed me. Not immediately, but over time. Like nearly everybody, I remember the day well. My wife drove me to work, our two year old in the back seat. For some reason the car radio had flipped to a Spanish station and they were talking excitedly. Nicole went to change it and I joked no, leave it there, give our daughter some exposure to Spanish.

“What do you think they are so excited about?” Nicole asked.

I walked into the office, ready to crank out some educational software and saw people huddled around some of the TVs we used for previewing educational video clips.

“What’s going on?” I asked, seeing the now famous footage on TV.

“Basically, we’re under attack.” said one of my co-workers.

I was a libertarian anti-war kid who believed most geo-political threats were blown out of proportion, who had opposed everything from the Gulf War to Kosovo, and openly scoffed at Clinton’s attempted Bin Laden strike as a wag-the-dog response to the Lewinsky scandal. I didn’t become a pro-war booster, of course, but the experience shattered my ideological simplicity. Temporarily, at least, it made me less vocally anti-war. Again, not pro-war — but far less confident about my own opinions for a short period of time.

That day is the big one for a lot of people, but think of how many other events shaped your life. The death of Heather Heyer in Charlottesville. The shooting at Tree of Life. Dylann Roof and that Confederate flag. The images of Katrina. The pepper-spraying of students at UC Davis. The shooting of Philando Castile. The Access Hollywood bus tape.

It would be folly, I think, in a world where the gender gap in politics has reached historic levels, to think that that Access Hollywood tape hasn’t had a part in framing what has come since. That Heather Heyer’s death didn’t push the ACLU to rethink its mission. That Castile’s death didn’t alter, at least incrementally, the sense of urgency around police violence. That even smaller things — like the President’s comment that there were fine people on both sides — hasn’t altered the way we can frame and not frame events.

Political scientists are a cynical bunch about change and causality, but you won’t find political scientists that say that events don’t matter at all. Matter less than we think, matter only in certain circumstances. But from Watergate to the sinking of the Lusitania to Pearl Harbor to the death of Emmett Till, events have changed the political landscape in both subtle and profound ways.

These cultural experiences shape us and change what is politically possible. Not overnight, but, like the bankruptcy in The Sun Also Rises, gradually, then suddenly. Even 9/11, one remembers, found itself amplified by the DC sniper, the ricin letters, the slow confluence of events that built a narrative of a world out of control. Together they made it politically possible to advance a war that wreaked untold suffering on both Iraqis and our soldiers, that made leaders unembarrassed to share new waterboarding authoritarian fantasies with pride.

I didn’t support the Iraq War, of course. For me, it was a matter of disagreeing but too noncommittally. Too much deference to writers I should have ignored. Too much of the then Slate-inflected on-the-other-hand distance, from about 2001 to early 2003. For others, it moved them into far darker places from which we still have yet to escape. (Others of course, were not knocked off balance at all , and I salute them).

But added together, the shifts were enough to change history, not just of the U.S., but of the world.

And yet, for most people, their primary experience of these events was through screens, websites, and print. One of the defining emotional experiences of any person my age’s life, and it was essentially information.

Information Is Experience

Years ago, Baudrillard made a compelling argument that the nature of reality had shifted over the course of human history, due to a shift in the way simulation relates to experience. According to him, first order simulation — the more common simulation of the past — represents things but maintains a boundary. I draw a picture of you the best I can, and hang it up. I make a map of the road to my house and hand it to you. You look at these as copies of reality and judge the fidelity of them to the source.

We’ll skip over second order simulation, to jump to this: by the time you get to third order simulation, the relationship of mediation to what is “real” has changed. The simulation doesn’t mediate reality as much as create it. For the vast majority, the reality of most of what you know about 9/11 or Charlottesville or Castile is never verified against any non-mediated reality. In turn, that created reality informs your physical experience, rightly or wrongly. My perspective of a recent “patriot” group that came onto campus, for example, was more influenced by the death of Heather Heyer than anything that happened on campus, and the digital reality I had been exposed to shaped that experience.

In the world of Baudrillard’s hyperreal, information is experience. And as such, the standard old-school experimental psychology tests — “Here’s some information about global warming, how do you feel about regulation now?” and the standard negative campaigning studies don’t really apply to what where seeing right now. They don’t even come close.

Digital Experience Frames Non-Digital Experience

Imagine your parent dies, or, if you’ve been so unlucky, think back on the death of a parent. This is an event that seems relatively unmediated, very real, very raw.

But what if you had found out, directly after their death, that the death was not inevitable? That as a matter of fact your parent had been misdiagnosed, was not in fact sick at all, and had been prescribed an accidentally lethal dose of medication by a doctor too drunk to even stand up?

Would your life change? Would it be different? Would your perspective on health care change? Would your narrative about this your parent’s life change? Would your identity change?

Some varieties of experimental psychology applied to disinformation would say no. It’s just information, it doesn’t change your opinions or beliefs. But of course it’s not just information. It’s experience, and the experience of having a parent die due to the negligence of a drunk doctor is fundamentally different than the experience of believing they died of lung cancer caused by earlier smoking.

If this seems over the top, consider that this is the experience of parents who have kids with autism, who daily must convince themselves that their child’s lifetime of struggle is not due to their decision to vaccinate them, or the greed of Big Pharma. It’s the experience of a person who doesn’t get a needed job and believes it is due to affirmative action policies they’ve read about, meme-ified across the web.

And it’s the experience of Chapian, where the stuff that she is reading online connects with nothing in her life, and yet it is the digital world that is more real.

This is not just about Chapian, of course. It is an unavoidable consequence of the world we inhabit. I care deeply about children separated at the border, have broken down in heaving sobs over the Tree of Life slaughter. Yet, the realness of these things for me is not as much mediated as it is created by the media I consume, and my experience of that reality is not fundamentally different than local events I hear about.

This is not necessarily a bad thing — as a person with a great deal of privilege, to trust only what is outside my window as reality would be ethically dubious at best. But the stream of digital information that reaches people is experience, both on its own — without any connection to daily life whatsoever — and as powerful frame for what they experience daily. Mucking with that stream of information doesn’t just change what I know, it changes my life history. It changes what happens to me.

Not What Would It Mean To Believe, But What Would It Mean To Experience

There’s benefits to separating belief and experience of course in analysis of course. But when thinking about disinformation I wouldn’t start with belief. I’d start with thinking about experience.

Not “what does it mean to believe crime is skyrocketing”. But “what would be the effects of skyrocketing crime on a population?” Not “what would it change if people believed migrants were threatening people in the street”, but instead “how would politics change if migrants were threatening people in the street?” Not “what would it change if people believed Monsanto was poisoning our cereal?” but instead “what would be the impact on your trust of corporations if you were personally poisoned by Monsanto?”

It seems a small change, but it will help you better understand how much of the most effective disinformation works, not by providing us with information, but by hacking the simulation that we must necessarily inhabit, and mucking with our experience, and thereby changing the realities that we are willing to accept.

Take for example this:

Chapian looked at the photo and nothing about it surprised her. Of course Trump had invited Clinton and Obama to the White House in a generous act of patriotism. Of course the Democrats — or “Demonrats,” as Chapian sometimes called them —had acted badly and disrespected America. It was the exact same narrative she saw playing out on her screen hundreds of times each day, and this time she decided to click ‘like’ and leave a comment.

“Well, they never did have any class,” she wrote.

from ‘Nothing on this page is real’: How lies become truth in online America (WaPo)

It’s a guess of course, but I’m going to guess that Chapian knows at least some Democrats, but that given her level of interaction with Facebook and her lack of interaction with others it is more likely that what she reads on the web alters her experience of those people more than her relationship with those people informs her experience of the web. The same would be true of immigrants, communities of color, and so on.

As she reads, she is not simply learning new information — she is repeatedly having enraging experiences with Democrats, Jews, migrants, Hollywood celebrities and others, and each bad experience does not ground to some mediated but ultimately singular reality. Instead, it grounds to a rich texture of other digital events which have formed her set of impressions. It’s believable the Democrats flipped off Trump because — well, all of your life experience supports it. I mean, for starters, Jay-Z rapped “middle finger to the lord” at a Clinton rally:

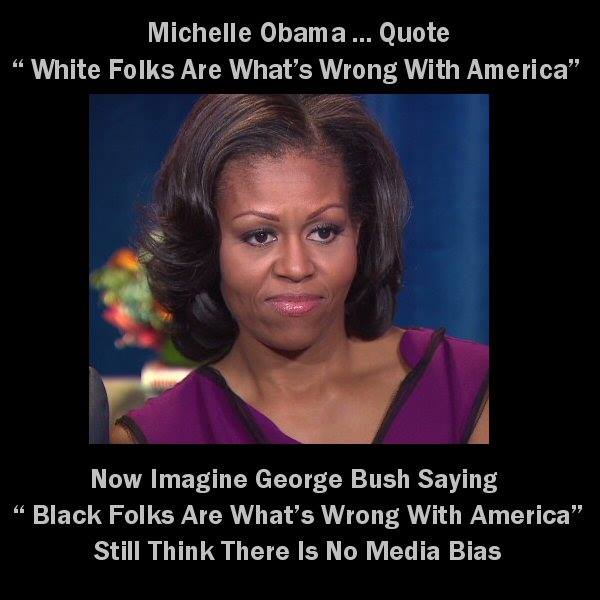

Michelle herself said “White folks are what’s wrong with America”

And Obama was caught on a mic saying that

“These crackers got no idea what it’s like to feel the struggle. Speakin’ of, how you gonna keep all your n*ggas in line while whitey Trump rules the roost?”

– Last Line of Defense, 18 January 2017

This is all false, of course, but Chapian experiences it at the level the average American experiences child separation policy at the border, the Access Hollywood tape, or far-right violence. The information is false, but each experience is real. And because of the phenomenon of hyperreality, she is more likely to trust her digital experience than her non-digital experience. She simply has accumulated far more influential experiences online, and to the extent that her online experience differs from other mediated realities, it’s the non-digital that is seen as not fitting:

For years she had watched network TV news, but increasingly Chapian wondered about the widening gap between what she read online and what she heard on the networks. “What else aren’t they telling us?” she wrote once, on Facebook, and if she believed the mainstream media was becoming insufficient or biased, it was her responsibility to seek out alternatives.

from ‘Nothing on this page is real’: How lies become truth in online America (WaPo)

So What?

The story above is for a trivial thing, of course — the rudeness of Democrats. But it’s the same process for pulling people into conspiracy theories about immigrants or Jews or the Deep State. It’s the same process by which many Democrats came to believe that Clinton had hacked the results of voting machines in the primary to hand her wins in Arizona, or that the White Helmets are really CIA agents.

See, even there I slipped — I let language minimize and constrain. “[T]he same process by which many Democrats came to believe that Clinton had hacked…” No. It’s the same process by which many Democrats came to experience the primaries as hacked by Clinton. See the difference?

Maybe this all seems like a trivial distinction to you. Maybe you already know this. I’m deep enough into this field that it is hard for me to tell what is common knowledge out there and what is not. Or maybe you think this conception is far too out there — though if that’s the case, I beg you to read the Washington Post article after this and reconsider.

But whatever your take, I encourage you to think of disinformation in this way, at least for a bit — not as the spread of false information, but as the hacking of the simulated reality which we all must necessarily inhabit. As something that does not just change knowledge, but which produces new life experiences as real as the the Iraq War, your neighbor’s fight with cancer, or your child’s illness. To see it in this way is perhaps more terrifying, but ultimately necessary as we attempt to address the problem.

Leave a comment