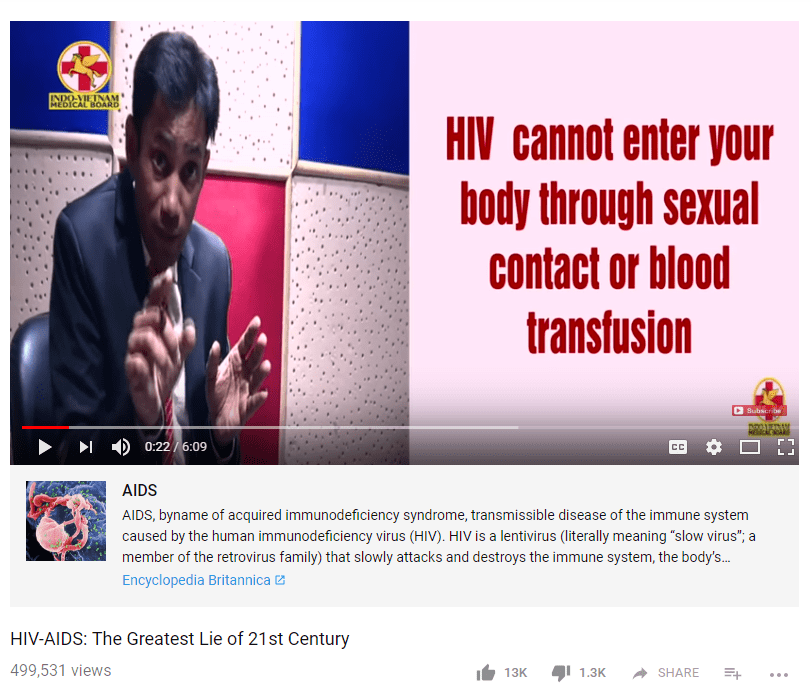

I was putting together materials for my online media literacy class and I was about to pull this video, which has half a million views and proposes that AIDS is the “greatest lie of the 21st century.” According to the video, HIV doesn’t cause AIDS, retrovirals do (I think that was the point, I honestly began to tune out).

But then I noticed one of the touches that Google has added recently: a link to a respectable article on the subject of AIDS. This is a technique that has some merit: don’t censor, but show clear links to more authoritative sources that provide better information.

At least that’s what I thought before I saw it in practice. Now I’m not sure. Take a look at what this looks like:

I’m trying to imagine my students parsing this page, and I can’t help but think without a flag to indicate this video is dangerously wrong that students will see the encyclopedic annotation and assume (without reading it of course) that it makes this video more trustworthy. It’s clean looking, it’s got a link to Encyclopedia Britannica, and what my own work with students and what Sam Wineburg’s research has shown is that these features may contribute to a “page gestalt” that causes the students to read this as more authoritative, not less — even if the text at the link directly contradicts the video. It’s quite possible that the easiness on the eyes and the presence of an authoritative link calms the mind, and opens it to the stream of bullshit coming from this guy’s mouth.

Maybe I’m wrong. It seems a fairly easy thing to test, and I assume they tested it. But it’s also possible that when these things get automated the things you thought were edge conditions turn out to be much more the norm than anticipated. In this case, the text that forms that paragraph from Britannica is on “AIDS”, not “AIDS denialism”, and as such the text rebuttal probably has less impact than the page gestalt.

I get the same feeling from this one about the Holocaust:

What a person probably needs to know here is not this summary of what the Holocaust was. The context card here functions, on a brief scan, like a label, and the relevant context of this video is not really the Holocaust, but Holocaust denialism, who promotes it, and why.

Again, I hope I’m wrong. Subtle differences in implementation can matter, and maybe my gut on this is just off. It really could be — my job involves watching a lot of people struggle with parsing web pages, and that might warp my perspective.

But it should be easy enough for a researcher to take these examples and see how it works in practice, right? Does anyone know if someone has done that?

Leave a reply to mikecaulfield Cancel reply