Phil Hill continues to do some of the best data journalism in educational technology. His last piece is a tour de force, marshalling data to show that students spend much less on textbooks than the current figures bandied about would indicate.

I think he’s right on that point, but I also think readers of that piece are likely to take away the wrong conclusion from Phil’s figures (even if Phil himself does not). So I’d like to introduce a parable here to explain why asking what students spend on textbooks is the wrong question, and then follow up with a bit of data of my own that I think may shock you.

First, the parable.

The Island of Perdiem

On a small island called Perdiem, a nearby war has disrupted normal commerce and the ships that used to bring food from the mainland no longer come.

Food prices spike. The island is an ally of the U.S., so a debate in Congress breaks out as to whether Perdiem is in a food crisis, and if so should the U.S. intervene? Are food prices there really at crisis levels?

They send a fact-finding team there, and initially they are shocked at what they see. On an island with a median income matching the U.S.’s, cucumbers are $5 a pound. Meat — of any sort — is $25 dollars a pound. Potatoes, a local staple, are $100 a bag. All around people are gaunt, and starving. It looks like it truly is a pricing crisis after all.

That’s when the committee chairman makes a startling realization. He starts asking the Perdimians how much of their monthly budget goes to food.

It turns out that while prices are five times higher, the Perdimians as a culture eat only a fifth of the calories of the average American eats. (What a weird coincidence!) And when you calculate this all out, it turns out that they spend about the same on food as Americans.

Well, that’s a funny sort of crisis he thinks — clearly this crisis is overblown. They head back to The U.S., relieved that all is well. The gaunt and quizzical Perdimians wave to them as their plane takes off.

Start With a Bag of Groceries

I’m sure you get the point of the parable, so I won’t belabor it. If we’re looking to find out if prices for some set of goods are too high, then by definition we cannot look at what people are spending as a reliable gauge, because one of the big effects of “prices too high” is that people can’t afford what they need.

If you don’t pay attention to this you get in all sorts of tautologies. Is food too expensive for minimum wage workers? Nope — it turns out they spend a lot less on food than the middle class, so it all works out. Were lower-class black children getting the care they need under the pre-Obamacare system? Absolutely — in fact their health care spending was the *lowest* in the nation!

A better approach to problems like the Island of Perdiem is to start with a bag of goods. We decide what it would take to keep you healthy for a week, take into consideration valid local substitutes, then look at the price of the bag. Then we look at what people are spending per week.

In a cash-strapped system, that difference between the price of the bag and the price people are spending on groceries is what we’ll call the food budget deficit — the amount of extra money people would need to eat healthy.

So let’s assemble a bag of textbook goods for our student, shall we?

Our Textbook Bag

So what should go into our bag of textbooks?

To create our bag, I went and got the first year suggested schedule for a math education major here. I then went to the bookstore and tallied up the price of all the required and recommended texts for my first year of courses (I did not include optional texts).

For each textbook I added two prices — the first price was for the cheapest version, which in most cases was a three-month textbook rental of a previously used textbook. The second price was for a new textbook.

The bag here also includes one $35-$50 clicker that is bundled with the textbooks — subtract that if you think that’s unfair.

Semester One:

Only four classes our first semester, two have labs bringing us to 14 credits. Light semester on books, then, which is good.

* Biology 101 (Intro Bio): $72.05 – $96.05

* English 101 Composition: $48.60 – $108

* History 105 (Global Issues): $70.55 – $128.40

* Math 171 Calculus” $106.30 – $209.70

Buying new: $542.15 + 8.5% sales tax = $588.23

Buying cheapest option (renting used) if available: $297.50 + 8.5% sales tax = $322.79

Semester Two:

* CS 121: (Intro Programming): $15.40 – $34.20

* FINE ART 201 (Pullman): $100.19 – $217

* MATH 172: $106.30 – $209.70

* MATH 220: $99.45 – $221.05

* SOC 102: $37.80 – $94.50

Buying new: $776.45 + 8.5% sales tax = $842.45

Buying cheapest option (renting used) if available: $359.14 + 8.5% sales tax = $389.67

And the Final Figures?

Commenter GalleryP notes that the Calculus book if bought (not rented) can be used across two semesters. So we adjust our high end down, and knock our mix down by $103. Rentals stay the same. For more on this see Pill-Splitting the Textbook.

- One year of new textbooks: $1221.68 ($1430.68 – $209)

- One year of rentals (mostly): $712.46

- Mix, half rentals, half new: $968.07

So which figure do we use here? The chances of getting everything you need as a rental are low. Sure, you could be the super-prepared student who knows how to work the system and get them *all* as rentals — but not every student can be first in line at the bookstore. And the ones at the back of the line — guess their socio-economic class and first generation status?

This is a real issue, and it’s worth sticking with it a second here. I found myself going through this exercise and thinking — well, I can rent this here, and this one is a primary text, so I can probably find that online somewhere, and the only one that really NEEDS to be new is going to be that Calculus book (because new problem sets, plus I’m going to want to keep it).

And of course that’s me, thinking like a second-generation college student. I know where to skimp and where to spend. I know to get to the bookstore day one to get the rentals. As matter of fact I gave my daughter Katie the whole low-down on textbooks just last semester as she took her first college class: get the text before the class, rent things that aren’t reference works, look on Amazon for primary sources etc. I showed her how to determine whether getting a slightly different edition would impact her learning by comparing the syllabus, and helped her think through whether she was going to want to keep a textbook that she had spent time annotating (in which case buy it, and buy it new).

You could use skills like this to cobble together that bag of books and say *that’s* the true cost. Look what you can get your books for if you game the system right!

But to say that, you’d have to have learned nothing in the past decade about why students fail. Requiring a non-traditional student to cobble together a bag of half-priced textbooks the way a second-generation student might is setting them up for failure.

I think you have to assume you go at *least* half and half with rentals to new if we’re talking about creating a world where all students have a textbook in hand. So $1072 a year seems to me a minimum.

And frankly, the most straightforward option here, and the simplest for the first-generation student or the non-residential adult student to navigate, is to just buy all the books the teacher tells you to get, so honestly, if you care about equity and simplicity and the fate of non-traditional students, then you’re not off the hook. You *have* to wrestle with the $1430 figure, because every decision that a non-traditional student uses to get that price down is one fraught with risk.

The Affordability Deficit

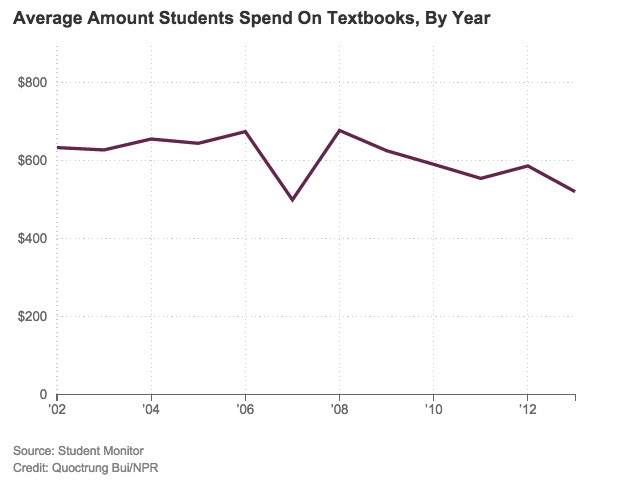

But wait — what about this chart, showing what students are spending? They aren’t even spending half that much!

If we really believe that the texts we assign in class are useful to the classes they are assigned, then what you see there is students hitting the ceiling of what they are able to spend on textbooks, a good $400-$700 before they have the books they need.

This should terrify you. That graph is a picture of the cost of textbooks preventing students from getting the materials they need to succeed.

You can do this yourself with classes if you want — I just used public facing Washington State University pages to make up our bag, with a randomly chosen major. Make up your own bag, at a different institution, with a different major. Do it in a state that makes textbooks tax-exempt — or for a real kick in the pants, put together a nursing degree. Share your findings!

What I think you’ll find out is that although there is a lot of variability in the cost of textbooks for a year in different degrees, the College Board estimate is much closer to estimating what students actually need than other measures offered.

Most of all, the two lessons here are that

- Under scarcity, the best picture of need is going to be calculated backward from what is needed, not what is bought.

- Protests that students “in the know” can make do can also doom students with less cultural capital to failure.

Thanks again to Phil for starting this conversation.

———–

There is an update to this in Pill-Splitting the Textbook, which deals with the issue of student strategies for buying, and how culture and access intersects with that.

Phil Hill replies in Asking What Students Spend On Textbooks Is Very Important, But Insufficient (and we’re basically in agreement).

Bracken replies in Delivering the Ideal Bag O’ Books, noting that we have to ask how to make the groceries even healthier.

David Wiley calls further attention to the impact of net getting the textbook, citing a study (also cited by Phil) in The Practical Cost of Textbooks.

Leave a comment