As we plan for our second fedwiki happening the differences between federated wiki and wiki become, well, stranger.

If you’ve been following the story thus far, you know that federated wiki is pretty radical already. As with wiki, people converse through making, linking, and editing documents. But because each person has a seperate wiki, there is a fluidity to this “talking in documents” that is hard to describe.

You write a post referencing Derrida’s concept of “ultimate hospitality”. I get interested in that, do a bit of research. I save a copy of (fork) your post to my site, but link it to a page describing Derrida’s hospitality in more detail. Not because I’m an expert, but because it’s a good excercise to understand your writing. You see that post and fork mine back. The next visitor to your page finds your page plus my article annotating it. Maybe they edit it, creating their own fork. And so it goes.

Carry It Forward or Clean Slate?

As we move into Happening #2 on Teaching Machines, this question comes up: do we pull these documents into the new happening? Use the same site? Do I create one big “Megasite of Mike” which I haul into each event like my persistent twitter feed?

And what we’re thinking is maybe I don’t. Maybe Happening #1 site is done, and I create another site.

So for instance, my wiki farm is at hapgood.net. For Happening #1 on “journaling” I had journal.hapgood.net. Maybe for the Teaching Machines happening I make machines.hapgood.net. And to the extent I want to talk about something from a previous event in this new context, I fork it into the new context.

It’s pretty simple to do this in Federated Wiki after all. I just drag the page from one site and drop it on another, I edit it for the new audience, or maybe even take the opportunity to clean up a few typos. And that’s it, done!

While this may not sound extraordinary, it is in fact an inversion of how we usually think of wiki (and sites in general). And it has some neat ramifications.

The Dreaded Curve of Collaborative Sites

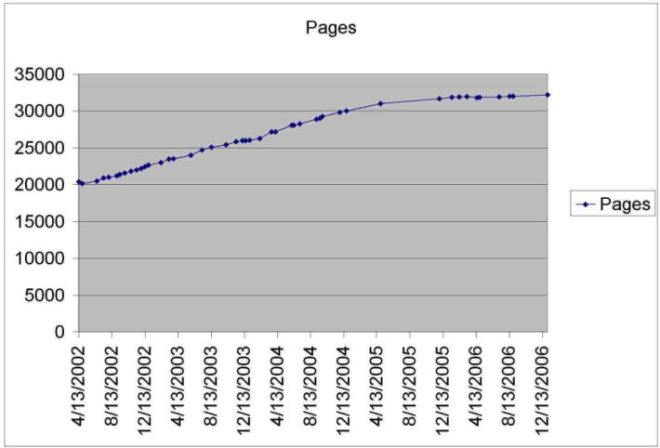

To understand why this is such a departure from traditional collaborative sites, we need to introduce you to the dreaded logistic curve. Here’s the curve of Wikipedia production:

Via Wikimedia Commons.

Until about March 2007 many people thought that Wikipedia’s growth was exponential. Above, we see a log scale graph, where exponential growth would be represented by a straight line (explanation of log scale).

But things go a little wonky in 2007. In that year it begins to become apparent that a logistic model might better predict Wikipedia growth. Currently the site is growing faster than a logistic model would predict, but well under earlier exponential models.

“Enwikipediagrowthcomparison” by HenkvD

If the extended model above fits, Wikipedia will near heat death in about 10 years.

Projection by HenkvD

People have attributed this to a lot of things, and certainly it’s a phenomenon with many inputs. But the logistic-like nature of it suggests one simple explanation — limited resources. Logistic curves are what you find when you map animal populations, for example, coming up against the resource limits of the environment.

In wiki, as in many other collaborative projects, the limited resource is stuff left to be written. People get together to write articles, and initially each new article leads to two other articles, and you see that growth on the left side of the graph.

Eventually, though, the easier stuff is written. It may not be written the way you’d like it to be, but it’s written. Wikizens move from homesteading new territory to vicious fighting over already cultivated plots of land. The enterprise begins to feel less fresh, and the type of people who find this stage envigorating are often dreadful bureaucrats.

Now, you might think this was just a function of Wikipedia, as it has articles on everything. But you’d be wrong. Smaller wiki communities see this same pattern. Here’s a graph of the first wiki approaching its own heat death:

(Chart by Donald Noyes)

Now these are the tail-end days of that wiki — it started in 1995. And its this observed pattern that led Ward Cunningham to predict, much earlier than most, that Wikipedia would follow the same pattern.

Colony Collapse

We get why Wikipedia would hit a resource limit — there’s an article on fish fingers already, for crying out loud. But why would WikiWikiWeb run out of subjects? There’s only 30,000 pages, after all.

The answer’s simple — people come together for a reason, a shared interest. In the case of WikiWikiWeb it was to share software design patterns and agile programming techniques. As those subjects fill out, the opportunities for new contribution diminish. The community has a choice — expand its charter (which fractures the cohesion of the group) or move into maintenance mode. (Likewise, Wikipedia could expand its charter by loosening notability requirements, for example, but this would radically change the nature of the project people thought they were contributing to).

Very few people want to be on a site that’s all about maintenance. As we mention above, the lack of new ground to cover leads to a claustrophobia manifested in endless arguments about what should and shouldn’t be on the wiki and non-stop edit wars.

This happens in other communities too, by the way. At some point in a political forum if there isn’t new blood people feel like they are just rehashing the same conversation over and over.

And so you get what I call Colony Collapse. One day you reach a tipping point, and suddenly the only people left on your site are the people you actually considered banning at the beginning. (This is what has happened to my old political community). For a while these people maintain the site, but eventually they too get bored and leave, and the site falls into disrepair. It starts to rot.

You can see this at my old site Blue Hampshire, which has reached the final phase of collapse, and now consists primarily of syndicated political press releases and occassional comments about how moronic other commenters are. There’s 8 years of beautiful posts in that site, almost 15,000 posts. Many contain wonderful explanations on how New Hampshire government works, personal reminiscences of New Hampshire political history. There are comments on that site with more political wisdom then you’ll find in a year of the Washington Post (there’s over 100,000 comments).

And it’s all rotting.

It’s heartbreaking, and after you’ve been through it once you get into a feed-the-beast mentality about all future communities. To paraphrase the line from Annie Hall: Online communities are like sharks; they have to keep moving forward or they die. And so, as community leader, you take on the exhausting role of the shark, pushing the site forward, always watching for the dreaded inflection point which presages the site’s collapse. Because once that happens, it’s all over.

A Different View: Wiki Sites as Bounded Conversations

That’s a long digression. But back to federated wiki.

Here’s a possible vision for federated wiki sites that you, the user make.

You’ll make federated sites for conversations on things, the way we are having this happening on Teaching Machines. And during the event, you’ll build it out. And then, at a predetermined point, you’ll call your personal version of that site done and abandon it.

In other words, we bake heat death into the plan. We accept our mortality.

That’s great, but now comes the question — how does the material get maintained? How do we recurse over it?

The answer we’re coming up with is that it gets pulled into new sites belonging to new conversations.

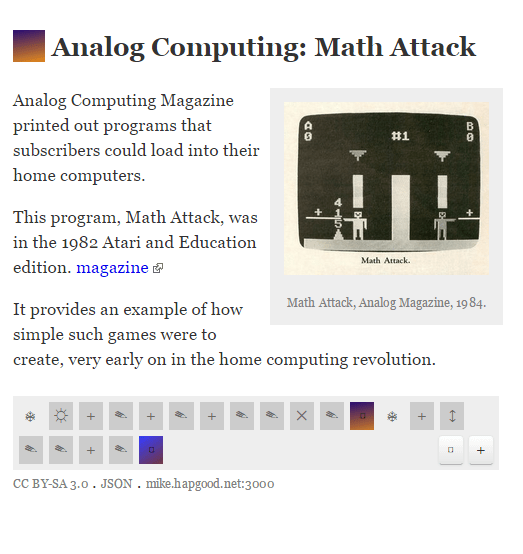

We have an example of this right now. We tried an experiment a while back that was a bit of a flop — a wiki called the “Hidden History of Online Learning”. It’s got about a hundred pages of this variety in it:

The site flared up into activity for a couple of weeks, then sputtered and died. By all normal metrics it’s a failure, doomed to bit-rot and link-rot, a slow descent into a GeoCities-like hell.

But in this case everyone involved has their copy of the site. As they participate in the Teaching Machines happening, they can pull stuff over into the new teaching machines wiki they have made. They’ll spruce it up, check the links, and maybe even improve it a little.

Ward and I were talking about this, and he said it reminded him of an earlier time when he was first working with Smalltalk. Objects would get better the more systems they were used in, because each time they were reused they would get refactored, optimized, simplified, extended. He and his fellow coders even had a name for this: “Reverse Bit-rot”.

It shouldn’t happen. It defies the entropy we see in all those pretty graphs up-page. But it happened.

Maybe this can happen here too. Sites can end, like conversations end. But we reach back into those previous conversations and say — you know, we were talking about that a couple months ago, let’s pull this thing in. And that thing gets another spin.

Maybe this doesn’t sound radical to you. Maybe it sounds ordinary. But I am sure every former online community manager out there understands just how radical this idea is. It’s equivalent to the soft-forking solution that was adopted Live Journal that became *the* solution for the non-collaborative communities that followed. But here it is applied to collaborative tasks.

In this world, sites like Blue Hampshire die — and maybe even die quicker, more humane deaths. In fact, maybe we say, hey, here’s a site that is going to exist just for the 2008 election. Two years later you spin up a site on 2010. Four years later on 2012. Some material from 2008 flows in. Some doesn’t. If the material is good enough to live on, there is no failure, no Colony Collapse.

Each wiki site is the product of a bounded conversation, expected to die, but also expected to be raided for the next conversation.

Kind of nice, right?

Leave a comment